Policy Brief:

COVID-19 and

People on the Move

JUNE 2020

Executive Summary

COVID-19 leaves few lives and places

untouched. But its impact is harshest for

those groups who were already in vulnerable

situations before the crisis. This is

particularly true for many people on the

move, such as migrants in irregular

situations, migrant workers with precarious

livelihoods, or working in the informal

economy, victims of tracking in persons as

well as people eeing their homes because

of persecution, war, violence, human rights

violations or disaster, whether within their

own countries — internally displaced persons

(IDPs) — or across international borders —

refugees and asylum-seekers.

The disproportionate impact of the COVID-

19 pandemic on people on the move

presents itself as three interlocking crises,

exacerbating existing vulnerabilities.

1

•

First, a health crisis as people on the move

nd themselves exposed to the virus with

limited tools to protect themselves. In addi-

tion to their often poor or crowded living

or working conditions, many people on the

move have compromised access to health

services due to legal, language, cultural

or other barriers. Particularly impacted

are those migrants and refugees who are

undocumented and who may face detention

and deportation if reported to immigration

authorities. Many people on the move also

lack access to other basic services – such as

water and sanitation or nutrition – and those

in fragile, disaster-prone and conict-affected

countries are facing higher risks owing to

weak health systems, which is compounded

by travel restrictions constraining delivery

of lifesaving humanitarian assistance.

•

Second, a socio-economic crisis impacting

people on the move with precarious live-

lihoods, particularly those working in the

informal economy with no or limited access

to social protection measures. The crisis

has also exacerbated the already fragile

situation of women and girls on the move,

who face higher risks of exposure to gen-

der-based violence, abuse and exploitation,

and have diculty accessing protection

and response services. Meanwhile, loss

of employment and wages as a result of

COVID-19 is leading to a decline in migrant

remittances, with devastating effects for

the 800 million people relying on them.

•

Third, a protection crisis as border closures

and other movement restrictions to curb the

spread of COVID-19 have a severe impact

on the rights of many people on the move

2 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

1 While all people on the move are equally entitled to the same universal human rights, the impact of these three inter-locking crises is not

uniform across the wide span of people on the move covered in this policy brief as it depends on the context, their socioeconomic situ-

ation and legal status under national and international law, as well as intersecting factors like age, gender and disability. While IDPs are

mostly citizens or habitual residents of their own countries and should have access to equal rights as their fellow nationals, international

migrants and refugees are distinct groups governed by different legal frameworks, with refugees entitled to the specic international

protection dened by international refugee law. Victims of tracking in persons are afforded specic protections as outlined in various

United Nations Conventions and Instruments.

who may nd themselves trapped in deeply

dangerous situations. Asylum-seekers may

nd themselves unable to cross interna-

tional borders to seek protection and some

refugees may be sent back to danger and

persecution in their country of origin. In

other instances, migrants may be forcibly

returned to their home countries with frag-

ile health systems, which are ill-prepared

to receive them safely, while returning IDPs

may face a similar predicament in their

home localities. Aditionally fear of COVID-19

is exacerbating already high levels of xeno-

phobia, racism and stigmatization and has

even given rise to attacks against refugees

and migrants. In the long-run there is a risk

that COVID-19 may entrench restrictions

on international movement and the cur-

tailment of rights of people on the move.

COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on

people on the move contrasts with their

outsized role on the frontlines of responding

to the crisis - highlighting their broader

contributions to societies around the world

- while caring for the sick and elderly or

keeping up food supplies during lockdowns.

Against this background, the COVID-19 crisis

presents us with an opportunity to reimagine

human mobility for the benet of all while

advancing our central commitment of the 2030

Agenda to leave no one behind. In the pursuit

of this objective, this Policy Brief offers four

basic tenets to guide our collective response:

1. Exclusion is costly in the long-run whereas

inclusion pays off for everyone: Exclusion

of people on the move is the very same

reason they are among the most vulnerable

to this pandemic today. Only an inclusive

public health and socio-economic response

will help us suppress the virus, restart

our economies and stay on track to reach

the Sustainable Development Goals.

2. The response to COVID-19 and protecting

the human rights of people on the move

are not mutually exclusive: COVID-19

has not stopped people from eeing

violence or persecution. Many countries

have shown that travel restrictions and

border control measures can and should

be safely implemented in full respect

of the rights of people on the move.

3. No-one is safe until everyone is safe: We

cannot afford to leave anyone behind in our

response and recovery efforts, especially

those people on the move who were already

most vulnerable before the crisis. Lifesaving

humanitarian assistance, social services and

learning solutions must remain accessible

to people on the move. For all of us to be

safe, diagnostics, treatment and vaccines

must be universally accessible, without

discrimination based on migration status.

4. People on the move are part of the solution:

The best way to recognize the important

contribution made by people on the

move to our societies during this crisis

is to remove barriers that inhibit their

full potential. This means facilitating the

recognition and accreditation of their

qualications, exploring various models

of regularisation pathways for migrants

in irregular situations and reducing

transaction costs for remittances.

There are encouraging steps already taken by

many governments in this direction, some of

which are highlighted in this Brief. The four basic

tenets offered by this Brief are underpinned

by our collective commitment to ensure that

the responsibility for protecting the world’s

refugees is equitably shared and that human

mobility remains safe, inclusive, and respects

international human rights and refugee law, as

envisaged not least by the Global Compacts

on Refugees and for Safe, Regular and Orderly

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 3

Migration. They also reinforce the notion that

no one country can ght the virus alone and

no one country can manage migration alone.

But together, we can do both: contain the

virus’s spread, buffer its impact on livelihoods

and communities and recover better.

FOUR BASIC TENETS TO ADVANCING SAFE

AND INCLUSIVE HUMAN MOBILITY DURING

AND IN THE AFTERMATH OF COVID-19:

1. Exclusion is costly in the long-run whereas

inclusion pays off for everyone.

2. The response to COVID-19 and protecting the

human rights of people on the move are not

mutually exclusive.

3. No-one is safe until everyone is safe.

4. People on the move are part of the solution.

4 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

THREE CRISES IMPACTING PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

Protection crisis Socio-economic crisis

Health crisis

•

Unsanitary and crowded living conditions (e.g. some

refugee camps have a population density that is 1,000

times that of surrounding host communities.)

•

Compromised access to health services

•

Food insecurity (e.g. more than half of the world’s

refugees and IDPs live in countries and communities

that feature high levels of food-insecurity.)

•

Curtailed access to asylum an (e.g. 99 countries

are making no exceptions for admission of asylum

seekers at closed borders)

•

Detention, forced returns and deportations

•

Stranded migrants, family separation and human

smuggling

•

Rising unemployment and loss of livelihoods

(e.g. over half of the refugees surveyed by UNHCR in

Lebanon reported having lost their already meagre

livelihoods)

•

Decline in remittances (e.g. remittances will drop by a

total of USD$109 Billion in 2020 due to COVID-19)

Migrants, Refugees and Internally Displaced

Persons in Numbers

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 5

2 United Nations, Department of Social and Economic Affairs (2019), International Migration 2019, available at: https://www.un.org/en/

development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/InternationalMigration2019_Report.pdf

UNDESA

2

TOTAL NUMBER OF INTERNATIONAL MIGRANTS, 1990–2019 (MILLIONS)

1990 2000 2010 2019

153

173.6

220.8

271.6

International Migrants

Based on ocial government data, the number of international migrants at mid-2019 is estimated to be around

272 million persons, dened for statistical purposes as persons who changed their country of residence,

including refugees and asylum-seekers. Since 1990, the global number of international migrants has

increased signicantly faster (78 per cent) than the global population (45 per cent). The share of international

migrants in the total population increased by more than six percentage points in Northern America, by

around four percentage points in Europe and Oceania, and by more than three percentage points in Northern

Africa and Western Asia. In other regions it remained stable or declined slightly (United Nations, 2019).

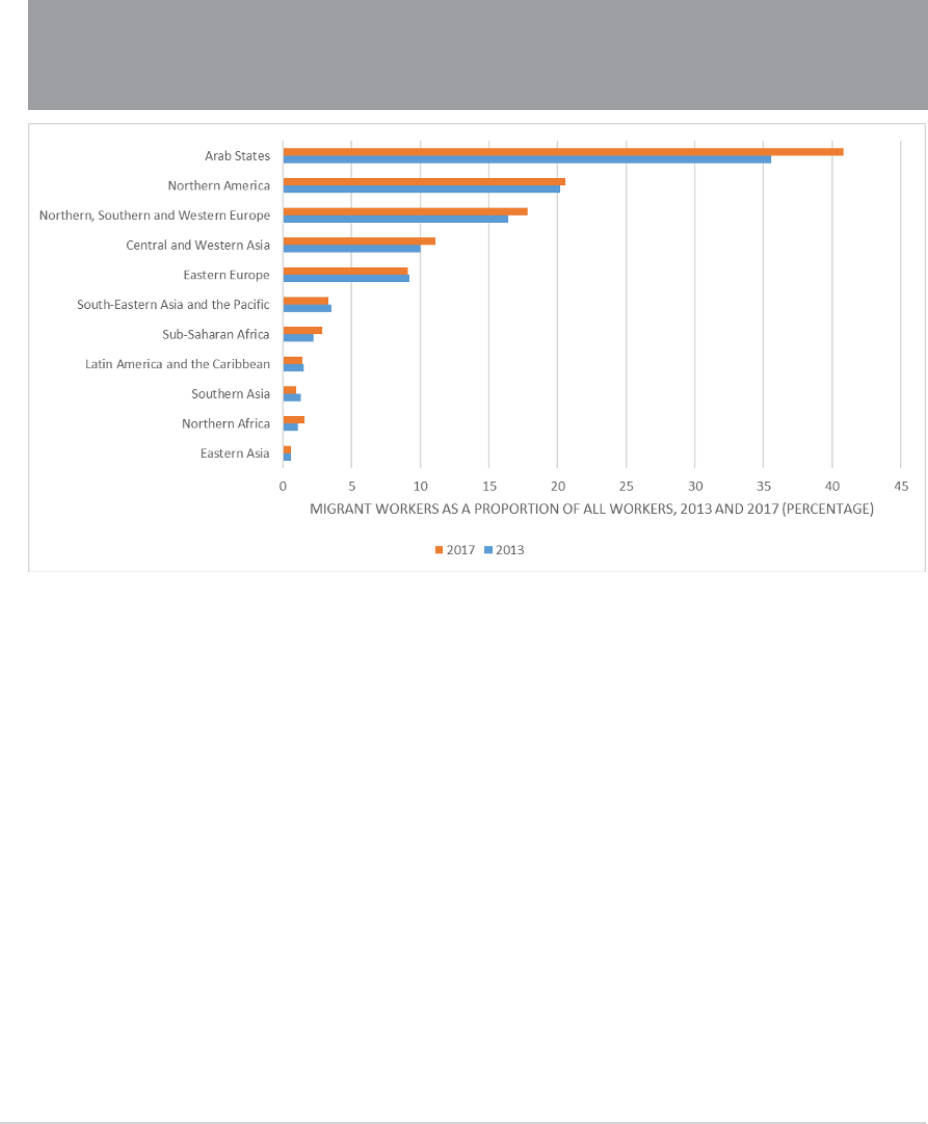

International Migrant Workers

According to the International Labour Organisation, globally there are 164 million international migrant workers

around the world. In terms of the share of migrant workers in all workers, gures are highest – and have been

increasing in recent years - in Arab States, Northern America, Western Europe, and Central and Western Asia.

6 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

Source: ILO

MIGRANT WORKERS AS PROPORTION OF ALL WORKERS,

2013 & 2017 (PERCENTAGE)

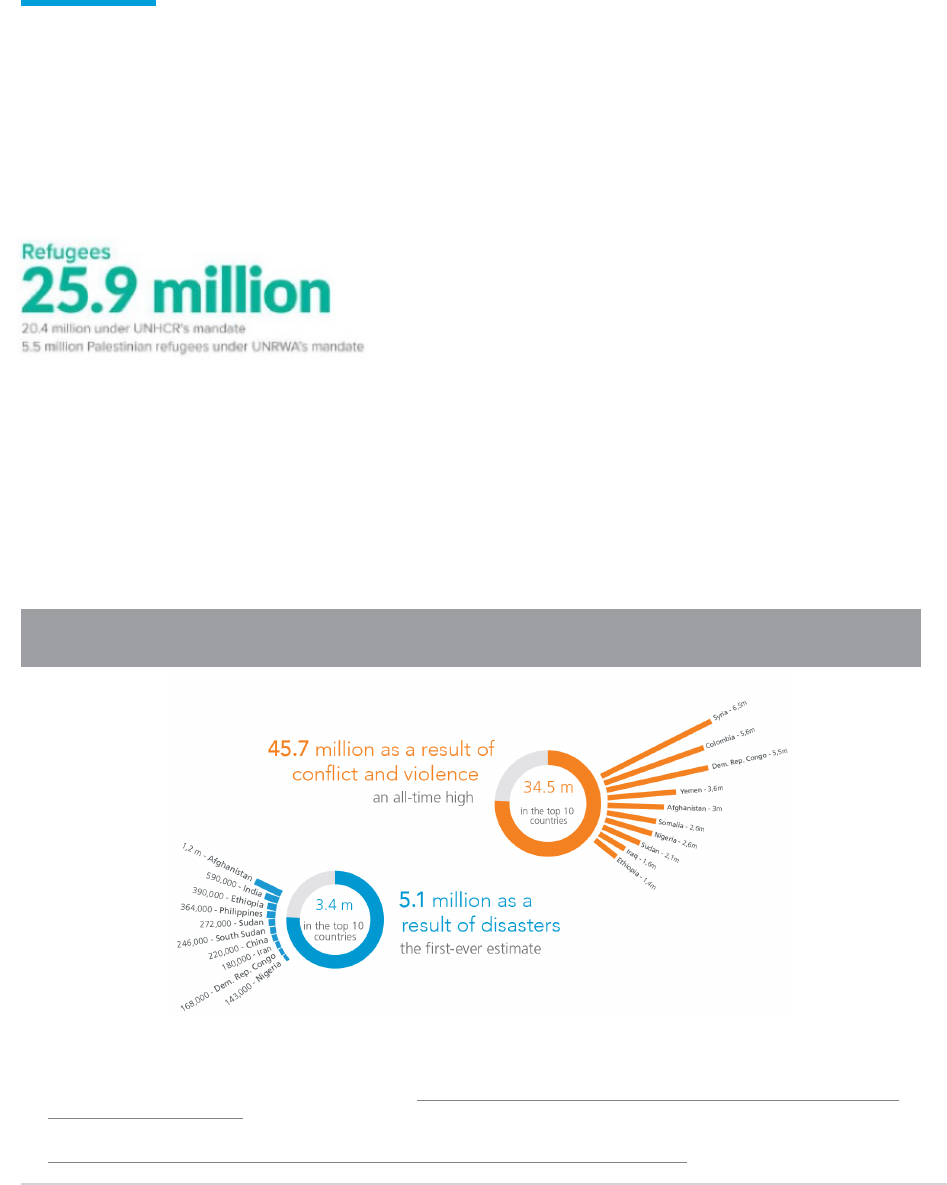

Refugees

The global refugee population stood at 25.9 million at the end of 2018 and is now at the highest level ever

recorded. Eighty-four percent of the world’s refugees are in countries in regions surrounding their countries

of origin, while one third (6.7 million) are in Least Developed Countries. Altogether, nine of the top ten

refugee-hosting countries were in developing regions and 84 per cent of refugees lived in these countries.

Internally Displaced Persons

The global number of Internally Displaced Persons is estimated at 50.8 million persons as of the end of

2019. 45.7 million are displaced as a result of conict, 5.1 million as a result of disasters. This number

has never been higher.

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 7

Source: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre

4

TOTAL NUMBER OF INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS

3 UNHCR (2019), UNHCR Global Trends Report, available at: https://www.unhcr.org/dach/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2019/06/2019-

06-07-Global-Trends-2018.pdf

4 Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) (2020), Global Report on Internal Displacement (2020), available at:

https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/2020-global-report-on-internal-displacement

Source: UNHCR

3

Migrants, Refugees and Internally Displaced

Persons in Numbers

8 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

1. The health and

humanitarian impact

People on the move in vulnerable situations

are particularly exposed to the health impact

of COVID-19. Many live or work in crowded or

unsanitary conditions where COVID-19 can

easily spread. Their access to health may be

compromised, particularly when they are

undocumented or excluded. They also often

lack access to other basic services – from

housing to water and sanitation, from food to

social services and from education to social

protection.

5

The health risks are compounded in fragile,

conict-affected and humanitarian settings,

in which large numbers of refugees and IDPs

live and where health systems are weak. While

recent reports of cases in crowded refugee and

IDP camps and settlements, such as those in

South Sudan, Bangladesh and Kenya, remain

comparatively low, there are fears that it will rise

in weeks and months to come, as capacities

to contain the virus and deal with its impact

are limited. For example, according to the

UN-OCHA COVID-19 risk index, which reects

both vulnerability and response capacity,

6

the

10 countries most at risk of COVID-19 host a

combined 17.3 million IDPs.

7

These risks are

compounded by weak health systems and

travel restrictions, which are severely impeding

access to lifesaving humanitarian assistance.

Urgent action to include people on the move and

their host communities in COVID-19 responses

and protect them from the pandemic’s worst

impact is in everyone’s best interest.

UNSANITARY AND CROWDED

LIVING CONDITIONS

AND LIMITED ACCESS

TO BASIC SERVICES

Many people on the move lack an adequate

standard of living which makes them extremely

vulnerable to the pandemic. IDPs, refugees and

many migrants – especially those in irregular

situations — live in crowded conditions — in

camps or informal settlements, in slums,

collective shelters, dormitories, immigration

detention centres, or situations of homelessness

- where washrooms, cooking and dining

facilities are shared, conditions are unsanitary

and physical distancing and stay-at-home

measures virtually impossible to implement.

For instance, Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya

has a population density about 1,000 times that

of the host Turkana community.

8

In Somalia,

there are around half a million IDPs who ed a

combination of conict and climate factors living

in crowded settlements throughout Mogadishu,

one of the fastest growing cities in the world.

5 OHCHR (2014), The Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of Migrants in an Irregular Situation, available at: https://www.ohchr.org/

Documents/Publications/HR-PUB-14-1_en.pdf

6 OCHA (2020), Global Humanitarian Response Plan Covid-19, available at: https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/les/GHRP-COVID19_

May_Update.pdf

7 Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) (2020), Global Report on Internal Displacement (2020)

8 https://sfd.susana.org/about/worldwide-projects/city/122-kakuma

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 9

Many people on the move also have limited

access to water, hygiene and sanitation, making

it harder for them to practice handwashing.

37 per cent of children and young people on

the move in the Horn of Africa do not have

access to basic sanitary facilities.

9

Access

is even further restricted for some people

on the move, such as women and girls,

older persons and those with disabilities.

COMPROMISED ACCESS

TO HEALTH SERVICES

IDPs, refugees and many migrants, especially

those in vulnerable situations, also face barriers

to accessing health services due to various

factors, including their migration status, lack of

awareness or social protection, costs, language,

disability, gender norms and cultural barriers, or

as a result of discriminatory laws, policies and

practices. In cases where no rewalls are in place

between immigration enforcement activities

and health services, refugees and migrants

who are in irregular situations or lacking proper

documentation may be unable or unwilling to

access health services, including testing, due to

fear of detention, deportation or other penalties.

People on the move also have limited access to

mental health and psychosocial services, which

have become all the more important as the crisis

exposes them to immense stress exacerbating

their already precarious conditions.

10

Furthermore,

the crisis has also disproportionately exposed

women on the move to health risks as they play

an outsized role in essential health services.

Compounding the compromised access to health

care of people on the move is their generally

limited access to critical health information, in

formats and languages they understand and trust.

Moreover, accessing health care and other basic

services is even more dicult for those who face

multiple and intersecting layers of discrimination

and exclusion in addition to their migration status,

due to their gender, sexual orientation, gender

identity, age, race and ethnicity, disability,

11

or

as a result of poverty, or homelessness.

Further, the disruption or discontinuity of

essential health services, including sexual and

reproductive health services, as a result of COVID-

19 will severely impact people on the move,

especially women, new-borns and adolescent

girls and those living in fragile, disaster-prone

or conict-affected countries. Reductions in

routine health service coverage could result in

an additional 1.2 million under-ve deaths in just

six months — with children on the move and in

conict-affected countries being most at risk.

12

RISING FOOD INSECURITY

People on the move in vulnerable situations

are also at greater risk of being affected by

COVID-19-related food insecurity resulting

from reduced agricultural activity, supply

chain disruptions, and price increases for

essential goods and a decline in purchasing

power due to the economic crisis. More than

half of the world’s refugees

13

and IDPs live in

countries and communities that even before the

9 UNICEF (2020), Children on the Move in East Africa: Research insights to mitigate COVID-19, available at: https://blogs.unicef.org/

evidence-for-action/children-on-the-move-in-east-africa-research-insights-to-mitigate-covid-19/

10 For more details see Policy Brief on COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health, available at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.

un.org/les/un_policy_brief-covid_and_mental_health_nal.pdf

11 For more details see Policy Brief on A Disability-Inclusive Response to COVID-19, available at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/

les/sg_policy_brief_on_persons_with_disabilities_nal.pdf

12 https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/covid-19-devastates-already-fragile-health-systems-over-6000-additional-children

13 50% of the world’s refugees are hosted in 8 food crisis countries: Turkey, Pakistan, Uganda, The Sudan, Lebanon, Bangladesh,

Jordan and Ethiopia. Global Network against Food Crises (2020), Global Report On Food Crises, available at: https://www.wfp.org/

publications/2020-global-report-food-crises

10 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

current pandemic featured high levels of food-

insecurity.

14

In East Africa, for instance, at least

60 per cent of refugees in the region are already

experiencing food ration cuts forcing them to

resort to alternative means to cover their basic

needs. Disruptions in children’s diets will result

in acute wasting and stunting among children on

the move, exposing them to a lifelong impact.

CONSTRAINED

HUMANITARIAN ACCESS

All of the above risks are compounded by the

diculty of delivering humanitarian assistance

to the world’s most vulnerable people on the

move in light of cancelled ights, closed borders,

lockdown, and some countries placing export

controls on medical supplies and equipment.

This impact is especially felt among refugees

and IDPs, most of whom are dependent on

humanitarian aid. Lockdowns and restricted

access to camps in countries, such as Iraq and

Nigeria, have meant that provisions of goods and

services to IDP populations have been reduced

or limited to ‘life-saving’ activities only. There are

particular concerns that delayed preparedness

and contingency actions will increase the risk

and vulnerabilities facing IDPs and refugees

in several countries in the coming months.

The mortality resulting from a combination of

constrained humanitarian access, increased

food insecurity and the economic downturn

may well outstrip that caused by the disease

itself. This reinforces the importance of

countries exempting humanitarian goods

and personnel from movement restrictions

and of Governments supporting the UN’s

COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan

along with existing Humanitarian Response

Plans to protect the world’s most vulnerable

people from the worst effects of COVID-19.

EXAMPLES OF GOOD PRACTICES IN

ADDRESSING THE HEALTH IMPACT OF

COVID-19 ON PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

• The UK government announced that no

charges will apply for the diagnosis or treat-

ment of COVID‐19 for all foreign visitors,

regardless of their residency/immigration

status.

• In Lebanon, humanitarian agencies and health

partners undertook outreach campaigns to

provide information to refugee populations on

COVID-19.

• Peru approved temporary health coverage for

refugees and migrants suspected of or testing

positive for COVID-19.

• Thailand has long allowed migrants in irregular

situation to enroll in the national health insur-

ance scheme, ensuring that they are provided

with universal health care.

14 WFP (2020), Global Report On Food Crises, available at: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000114546/

download/?_ga=2.210567581.944391335.1590667476-100388348.1590667476

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 11

2. The socio-economic impact

Necessary lockdowns, travel bans, and

physical distancing have brought many

economic activities around the world to a

severe slowdown, causing a global

recession. According to the International

Monetary Fund, the world economy is

expected to contract by 3 per cent in 2020.

Even countries with extremely low infection

rates will be severely hit by this economic

crisis. The World Bank estimates that

COVID-19 could push-up to 60 million people

into extreme poverty in 2020 alone.

15

Many people on the move tend to have few,

if any, reserves that might soften socio-

economic shocks. They are therefore among

the hardest hit by reduced incomes, increasing

unemployment, as well as increasing expenses

and price hikes for basic commodities. The crisis

has also exacerbated the already precarious

situation of women and girls on the move, who

face higher risks of exposure to gender-based

violence, abuse and exploitation, and have

increasingly limited access to protection and

response services.

16

Heightened stigma and

discrimination against persons with disabilities

within communities has also been reported.

Many migrant workers and refugees will

be deprived of their ability to contribute to

economic recovery in countries of destination

as well as to support families and communities

in their home countries. COVID-19 is projected

to result in a decline in remittances of USD$109

billion – equivalent to 72 per cent of total

ocial development assistance (ODA) in

2019 - causing hardship for the 800 million

people in those low-and-middle-income

countries that heavily depend on them.

17

At the same time, this crisis is an opportunity

for countries to ‘recover better’ through socio-

economic inclusion and decent work for people

on the move, and the provision of avenues for

regular migration. This will allow countries to

build on the positive contributions of people

on the move to their societies, which the

ongoing crisis has shone a light on. Indeed, as

recognized in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable

Development, human mobility is inextricably

linked with sustainable development.

RISING UNEMPLOYMENT

AND LOSS OF LIVELIHOODS

COVID-19-related movement restrictions and the

economic downturn are depriving many people

on the move of their livelihoods by threatening

jobs, particularly those in the informal sector.

15 https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/05/19/world-bank-group-100-countries-get-support-in-response-to-covid-

19-coronavirus

16 Protection Cluster Yemen, Preparedness and Response to Covid-19 - Protecting Groups at Disproportionate Risk, available at:

https://www.globalprotectioncluster.org/wp-content/uploads/Protecting-Groups-Preparedness-and-Response-to-Covid.pdf

17 World Bank (2020), COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens, available at:

https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/les/2020-04/Migration%20and%20Development%20Brief%2032_0.pdf

18 IOM, IOM Issue Brief on Why Migration Matters for Recovering Better from COVID 19, forthcoming

19 ILO (2018), Global Estimates on International Migrant Workers: Results and Methodology, available at:

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_652001.pdf

20 World Bank (2020), COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens

21 ILO (2020) Protecting migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_

protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_743268.pdf

22 Amo-Agyei, S. An Analysis of the Migrant Pay Gap, Technical Report, ILO Geneva (2020, forthcoming, available at https://www.ilo.org/

global/topics/labour-migration/; Data on informal migrant workers were available for 14 out of the 49 countries covered by the research.

Nationals also made up 70% of informal workers in the same countries examined.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS AND TARGETS RELEVANT TO MIGRANTS

Source: IOM

18

The 164 million migrant workers

19

and their

families around the world tend to be more

exposed to the loss of employment and

wages during an economic crisis compared to

nationals. For instance, during the 2008 global

nancial crisis, the increase in unemployment

of foreign‐born workers in the EU‐28 countries

dwarfed that of native‐born workers.

20

This is

due to a combination of factors, including the

fact that cyclical sectors (construction, service

jobs) were hardest hit, and that immigrants

are frequently the last hired and rst red.

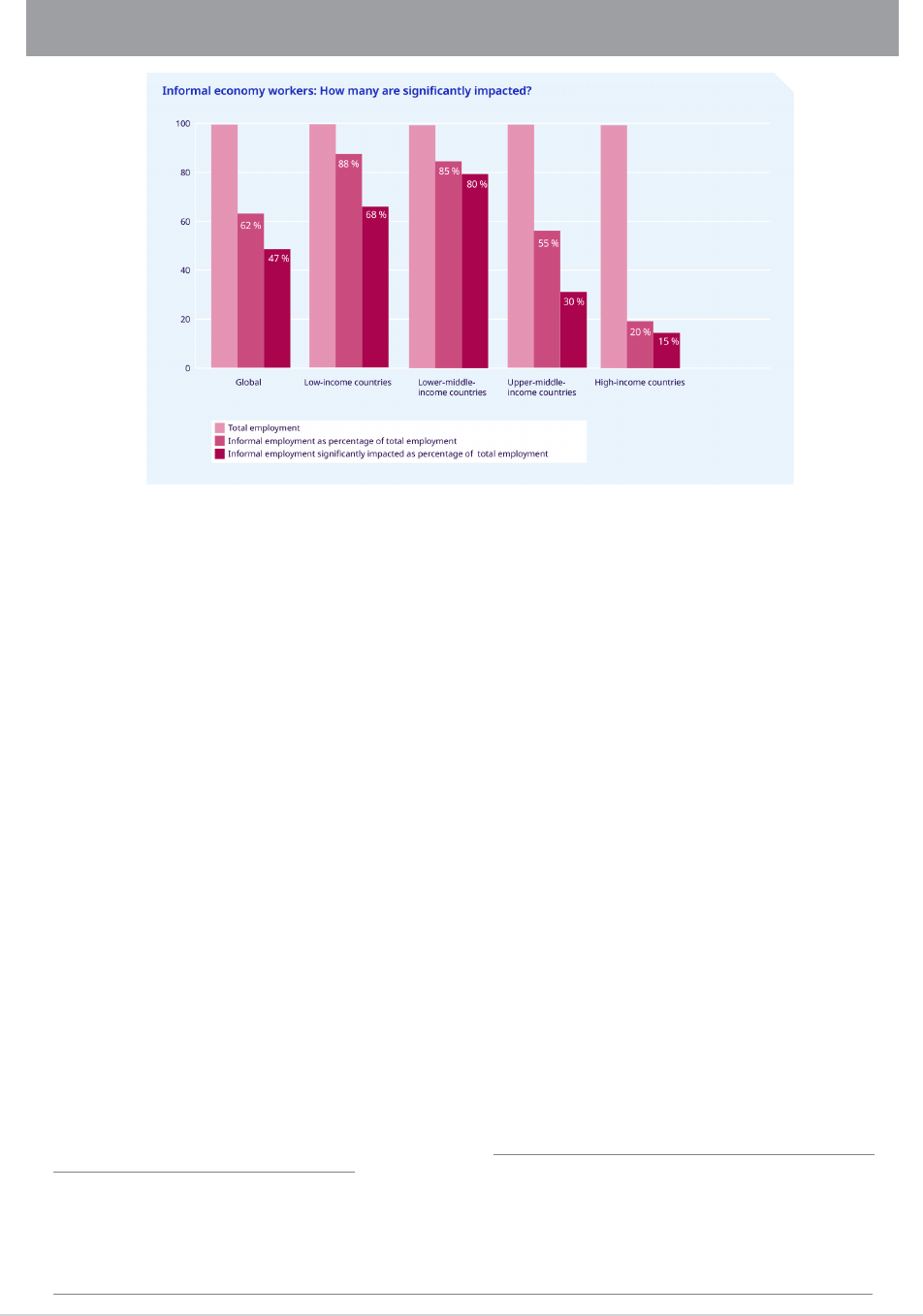

The pandemic’s socio-economic consequences

will affect in particular those migrant workers

and refugees in the low-wage informal economy

who are excluded from decent work and social

protection measures.

21

Recent ILO research

highlights the high incidence of informality

among migrant workers with nearly 75 per cent

of migrant women and 70 per cent of migrant

men working in the informal economy in many

low and middle-income countries.

22

With 30 per

cent of migrants being under 30 years of age, a

generation already faced with high youth unem-

12 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

ployment risks falling further behind. ILO esti-

mated that, in the second quarter of 2020 alone,

the drop of global working hours among workers

in the informal economy would be equivalent

to the loss of over 305 million full-time jobs.

23

In Libya, for instance, unemployment among

migrants rose from 7 per cent in February to 24

per cent by late April 2020.

24

Loss of employment among migrant workers

is compounded by the fact that they are

often not covered by protections of standard

labour law or social protection systems

and the risk that layoffs could trigger the

expiration of visa or work permits, forcing

them into undocumented or irregular status

or to return to their home countries.

26

IDPs and refugees are also hit hard by the

economic downturn. Across the Middle East

and North Africa, UNHCR and its partners have

received over 350,000 calls from refugees and

IDPs during the rst ve weeks of lockdown

asking for urgent nancial assistance to

cover their daily basic needs. In Lebanon,

over half of the refugees surveyed by UNHCR

reported having lost their already meagre

livelihoods, and 70 per cent reported that

they had to skip meals. In several countries,

movement restrictions imposed on IDPs

have impeded livelihood activities and

access to land for subsistence farming.

As demonstrated during the 2008 nancial crisis,

countries with strong social protection systems

and basic services suffered the least and

recovered the fastest.

27

As of 22 May 2020, 190

countries had planned, introduced or adapted

23 ILO (2020), COVID-19 and the World of Work: Third edition, available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/impacts-and-

responses/WCMS_743146/lang--en/index.htm.

24 Survey of 1,350 migrants conducted by IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) in April 2020.

25 ILO (2020), COVID-19 and the World of Work: Third edition

26 ILO (2020) Protecting migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic

27 UNDP (2010), The Global Financial Crisis of 2008-10: A View from the Social Sectors, available at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46468404_The_Global_Financial_Crisis_of_2008-10_A_View_from_the_Social_Sectors

IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON INFORMAL ECONOMY WORKERS (AS OF 29 APRIL 2020)

Source: ILO

25

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 13

social protection programmes in response to

COVID-19, with cash transfers being the most

commonly used measure.

28

However, migrant

workers and others in the informal economy,

including refugees, are often not included in

social protection measures. That lack of income

security creates a necessity to work while sick,

with potential consequences for everyone.

DISPROPORTIONATE IMPACT ON

WOMEN, CHILDREN, PERSONS

WITH DISABILITIES AND OLDER

PERSONS ON THE MOVE

Women and girls

29

on the move tend to be

particularly exposed to a number of specic

impacts of the pandemic. Women represent

approximately 42 per cent of all migrant workers

worldwide,

30

and play an outsized role in health

services, which disproportionately expose them

to health risks. Furthermore, owing to entrenched

gender stereotypes, women on the move also

carry the majority of the burden of both paid

and unpaid domestic and care work, which is

exacerbated by the quarantines. They are also

at heightened risk of gender-based violence, in

particular intimate partner violence exacerbated

by connement and lockdown measures.

31

Risk of sexual harassment and exploitation

in light of their often-crowded living and

unsafe working conditions are also increasing.

Moreover, female migrants and refugees often

face barriers in reaching out to police, justice

or gender-based violence (GBV) services,

particularly when they are undocumented,

for fear of retaliation, stigma, detention and

possible deportation, reinforcing the need for

‘rewalls.’

32

This situation is further exacerbated

by the fact that in some situations sexual and

gender-based violence protection and response

services have not necessarily been declared

essential, making it even more dicult for

women and girls on the move to access them.

Children

33

constitute more than half of the

world’s refugees and 42 percent of all IDPs.

34

The COVID-19-related lockdowns and the

economic downturn place many families on the

edge of survival, disrupting learning, children’s

diets and exacerbating protection risks for many

children on the move. The socio-economic fall-

out of the pandemic also increases the risk of

violence, abuse and exploitation, for instance

in the form of child labour, tracking for

sexual exploitation, or child marriage affecting

adolescent girls in particular. For example,

UNHCR reports an increase in cases of child

labour and child abuse among Syrian refugees.

1.5 billion young people, over 90 per cent of

the world’s students, in 188 countries have

had their education disrupted. For children

and youth on the move, this disruption adds

to an already precarious access to education.

Even before the pandemic, refugee children

were twice as likely to be out of school than

other children.

35

As access to schools is

curtailed, more children may drop out. Learning

28 http://www.ugogentilini.net/

29 For more details see Policy Brief on the Impact of COVID-19 on Women, available at:

https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/les/policy_brief_on_covid_impact_on_women_9_apr_2020_updated.pdf

30 IOM (2020), World Migration Report 2020, available at: https://publications.iom.int/system/les/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf#page=232

31 https://www.un.org/press/en/2020/sgsm20034.doc.htm

32 Global Protection Cluster (2020), Covid19 Protection Risks & Responses Situation Report No 2, available at:

https://www.globalprotectioncluster.org/2020/04/09/covid19-protection-risks-responses-situation-report-no-2/

33 For more details see Policy Brief on the Impact of COVID-19 on Children, available at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/les/policy_

brief_on_covid_impact_on_children_16_april_2020.pdf

34 UNICEF (2020), Lost at Home, available at: https://www.unicef.org/media/68826/le/Lost-at-home-risks-and-challenges-for-IDP-

children-2020.pdf

35 UNICEF (2017), Education Uprooted, available at: https://www.unicef.org/publications/les/UNICEF_Education_Uprooted.pdf

14 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

outcomes will worsen, and some will be

forced to work to offset economic strains,

potentially making a return to school after

the public health crisis subsides even more

dicult. Especially refugee or IDP girls may

never return to school. A whole generation

of young people on the move will struggle all

the more to nd jobs or start businesses.

Considering COVID-19’s disproportionally high

mortality rates among older persons,

36

older

people on the move are particularly vulnerable

to the pandemic’s health impact. This is further

exacerbated by limited access to health services,

accurate and reliable health information and

unsanitary living conditions, making this specic

group among the most exposed to the virus.

Persons with disabilities, including those who are

on the move, are also disproportionately affected

by the health impact of the pandemic, as they

are more susceptible to secondary conditions

and co-morbidities. Such impact is exacerbated

by the pre-existing inequalities faced by

persons with disabilities, including higher levels

of poverty and exclusion from education.

DECLINE IN REMITTANCES

The impact of job losses and reductions in

wages on migrant and refugee workers will also

be painfully felt by their families in their countries

of origin. According to the World Bank estimates,

remittances will decline by USD$109 billion

as a result of the pandemic.

37

Remittances

account for over 10 per cent of the GDP of 30

countries in the world

38

and are a critical source

of income for over 800 million people.

39

Early

data from Central American countries indicate

that remittances fell by 40 per cent in the latter

part of March.

40

Migrant workers’ reduction

in earnings is compounded by limited access

to remittance services due to lockdowns and

the fact that remittance service providers are

not considered essential businesses. Falling

business volumes and ongoing operating costs

could drive many of these remittance service

providers out of business, reducing market

competition and thereby impacting the global

efforts to reduce remittance transaction costs.

This resultant drop in remittances will also

impose economic hardship on the families and

communities of migrant workers, with direct

impact on household spending on education

for children of migrant workers and health care

in countries of origin. On average, 75 per cent

of remittances are used to cover essentials,

such as food, school fees, medical expenses

and housing.

41

This decline in remittances will

be all the more painful for many developing

36 For more details see Policy Brief on the Impact of COVID-19 on older persons, available at:

https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/les/un_policy_brief_on_covid-19_and_older_persons_1_may_2020.pdf

37 World Bank (2020) , COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens

38 IOM (2020), Migration-Related Socioeconomic Impacts of COVID-19 on Developing Countries, Issue Brief, May 2020, available at:

https://www.iom.int/sites/default/les/documents/05112020_lhd_covid_issue_brief_0.pdf

39 https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/remittances-matter.html

40 https://voxeu.org/article/perfect-storm-covid-19-emerging-economies

41 https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/remittances-matter.html

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 15

countries, particularly as direct foreign

investment is expected to fall by an even

larger share in 2020 than remittances.

42

THE CONTRIBUTION OF PEOPLE

ON THE MOVE TO SOCIETIES

The signicant impact of COVID-19 on migrant

workers and refugees notwithstanding, the

pandemic has shown the immense contribution

that these groups make to the societies they

live in. Millions of migrants and refugees are at

the frontline of the response or play a critical

role as essential workers, in particular in the

health sector, the formal and informal care

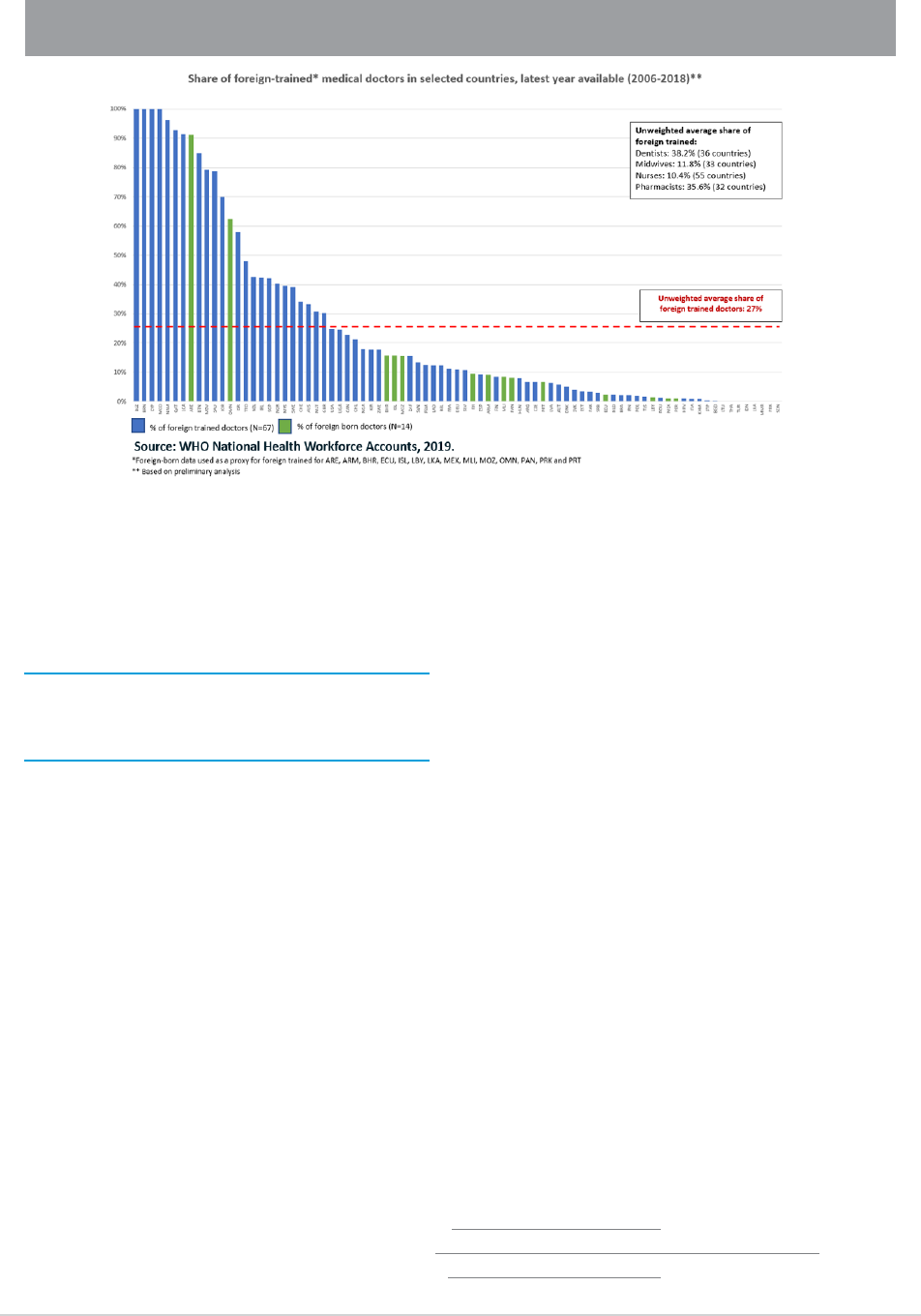

economy, and along food supply chains. Data

from over 80 WHO Member States indicate

that across countries over a quarter of doctors

and a third of dentists and pharmacists are

foreign-trained and/or foreign-born.

43

About

one in eight of all nurses globally is practicing

in a country different from where they were

born.

44

Migrant and refugee workers form

a signicant percentage of health workers

involved in the COVID-19 response in developed

countries. Across the globe, thousands of

migrants and refugees are working with national

health systems responding to the pandemic,

and several countries are accelerating

the accreditation of refugee and migrant

health workers so that they can contribute

to the response. While health workers are

considered essential, some of them remain

undocumented in the country where they reside.

The important contribution made by people on

the move to the societies they live in has also

been felt in other essential sectors, such as the

food supply chain. For example, the crisis has

42 World Bank (2020), COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens

43 Data extracted from the WHO NHWA Data Platform, available at: https://apps.who.int/nhwaportal/

44 WHO (2020), State of the World’s Nursing Report, available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/nursing-report-2020.

45 Data extracted from the WHO NHWA Data Platform, available at: https://apps.who.int/nhwaportal/

SHARE OF FOREIGN-TRAINED MEDICAL DOCTORS IN SELECTED COUNTRIES

Source: WHO

45

16 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

led to a shortage of seasonal farm workers in

the agriculture sector in North America, which is

heavily dependent on migrant workers. Similarly,

in Europe, there is an estimated shortfall of up

to one million seasonal agricultural workers.

46

This crisis therefore offers an opportunity to

evaluate the positive contributions of people

on the move to societies and the critical role

of migration in countries of destination more

broadly. For countries to “recover better”, it will

be important to explore further how to facilitate

the recognition of academic and professional

qualications earned abroad, include migrants

and refugees in social protection systems,

and facilitate safe, orderly and regular

migration so that societies may benet from

the full potential of migrants and refugees.

Similarly, record numbers of IDPs and refugees

continue to live in protracted displacement.

47

The response to COVID-19 has the potential

to strengthen efforts to end protracted

displacement and support durable solutions,

through economic and social integration,

and to inclusion of displaced persons in

national development plans. Earlier this year,

the Secretary-General launched a High-

Level Panel on Internal Displacement to

bring visibility to the issue and to elaborate

recommendations for improving the response

and achievement of durable solutions for

IDPs, which have become all the more

pressing in light of the current pandemic.

46 IOM (2020), Covid-19: Policies and Impact on Seasonal Agricultural Workers, available at:

https://www.iom.int/sites/default/les/documents/seasonal_agricultural_workers_27052020_0.pdf

47 OCHA (2017), Breaking the Impasse, available at: https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/les/Breaking-the-impasse.pdf

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 17

EXAMPLES OF GOOD PRACTICES IN ADDRESSING THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC

FALL-OUT OF COVID-19 ON PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

• Peru, Chile and Argentina recently began allowing foreign-trained refugee doctors, nurses and others with

medical training to work during the COVID-19 response.

• In Ireland, the Medical Council has announced it would allow refugees and asylum-seekers with med-

ical training to help in providing essential medical support by taking up roles, including as healthcare

assistants.

• Ukraine passed a law to ensure that IDPs receive social benets throughout the lock-down period.

• Humanitarian actors in Burkina Faso, Chad, Guinea, and Liberia continue to pay teacher incentives during

the closure of schools for refugee teachers to ensure continuity of income.

• The South African Government conrmed that 30 per cent of nancial support for small convenience shop

owners will go to foreign-owned businesses, including those owned by refugees.

• The Philippines is extending stipends to migrant workers to ensure that migrant workers are still able to

travel when they have valid employment contracts.

• Bahrain has established specic responsibilities for employers (and workers) in the private sector to

ensure appropriate accommodations and facilities for migrant workers during the pandemic.

• In Turkey, the government has long been providing training, certication and authorization for refugee

health professionals to practice in refugee health centres and deliver primary health care services to

refugees free of charge.

18 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

3. The human rights

and protection impact

As a result of COVID-19 international

mobility has been severely constrained with

often dramatic implications for people on

the move. In an effort to contain COVID-19’s

spread, countries around the world have

implemented border closures, travel

restrictions, and lockdowns. As of 21 May

2020, IOM reports that 221 countries,

territories and areas have implemented

travel restrictions.

48

While many of these measures have been

necessary in light of our collective struggle

against the pandemic, it is clear that keeping

human rights considerations at the fore

ensures better outcomes for everyone.

49

But the

impact on the human rights of people on the

move and the specic rights and protections

afforded to refugees and IDPs has not always

been suciently taken into account.

50

As a

result, many people on the move now nd

themselves trapped in deeply precarious

situations. People trying to ee persecution,

war, violence and other human rights violations

are prevented from accessing the protection

they need. Migrants, including unaccompanied

and separated children, have been deported to

their home countries, which are ill-equipped to

receive them in safety, or have been stranded

in border areas unable to return home.

Growing incidents of stigmatisation, xenophobia

and discrimination have in certain situations

led to forced evictions of refugees, migrants

and IDPs from their homes, leaving many

without shelter and prone to forced returns.

CURTAILED ACCESS TO

ASYLUM AND PROTECTION

Travel restrictions and border closures have

put the fundamental norms of international

human rights and refugee law under strain.

As of 22 May 2020, UNHCR reports that 161

countries have so far fully or partially closed

their borders to contain the spread of the virus.

At least 99 States are making no exception

for people seeking asylum seriously limiting

their rights. Denials of entry and pushbacks of

asylum-seekers and unaccompanied migrant

children at frontiers have been reported in

different regions and so have been refusals to

allow refugees and migrants rescued at sea to

disembark. In some cases, States have returned

asylum-seekers to transit countries to await

48 IOM (2020), Global Mobility Restriction Overview, available at:

https://migration.iom.int/reports/dtm-covid19-travel-restrictions-output-%E2%80%94-14-may-2020?close=true&covid-page=1

49 For more details see Policy Brief on the COVID-19 and Human Rights: We are all in this together, available at:

https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/les/un_policy_brief_on_human_rights_and_covid_23_april_2020.pdf

50 Zolberg Institute on Migration and Mobility (2020), Human mobility and human rights in the COVID-19 pandemic: Principles of protec-

tion for migrants, refugees, and other displaced persons persons signed by 1,000 academics from around the world, available at: https://

zolberginstitute.org/covid-19/

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 19

lifting of the restrictive measures, while in other

countries refugees were forcibly sent home in

violation of the principle of non-refoulement.

In addition, access to asylum procedures has

been hindered in some countries, while others

have suspended processes for providing

refugee or other forms of protection.

DETENTION, FORCED RETURNS

AND DEPORTATIONS

Government responses to COVID-19 have

also exposed migrants to increased risk of

immigration detention, family separation and

forced or risky returns without due process

and basic safeguards. Some States have used

public health concerns to justify certain types of

immigration enforcement measures, including

raids and arbitrary detentions of undocumented

migrants and refugees who are often held in

overcrowded facilities, with both detainees and

staff exposed to heightened risks of infection.

51

Several countries expelled and forcibly

returned migrants to States with fragile health

systems,

52

exposing them and their receiving

communities to serious public health risks.

53

STRANDED MIGRANTS,

FAMILY SEPARATION AND

HUMAN SMUGGLING

As borders were shut, many migrant workers

found themselves stranded in countries of

destination or transit, while others who lost

their jobs have had their visas revoked or

suspended and were placed in overcrowded

facilities before being returned home. COVID-

19 is also leading to protracted separation of

families on the move as family reunication

procedures are put on hold, or because families

are split across borders that remain closed

without allowing for humanitarian exceptions.

With borders closed, both refugees trying

to ee war and persecution and stranded

migrants desperate to make it home or to their

destination are more prone to seek the services

of human smugglers, exposing themselves to

the threat of human tracking, exploitation

and endangering their lives, as we already see

happening in different parts of the world.

54

Due to their more precarious working and

living conditions, undocumented migrants and

seasonal workers, especially those engaged

in domestic work, face greater vulnerability to

falling prey to criminal networks engaged in

tracking in persons. Further, with movement

restrictions diverting law enforcement resources

and reducing social and public services,

tracking victims face little hope of accessing

justice and essential services, with the closure or

reduction of specialized hotlines and shelters.

55

51 United Nations, Network on Migration (2020), COVID-19 & Immigration Detention: What Can Governments and Other Stakeholders Do?,

available at: https://migrationnetwork.un.org/sites/default/les/docs/un_network_on_migration_wg_atd_policy_brief_covid-19_and_

immigration_detention.pdf

52 R4V (2020), COVID-19 Update, available at: https://r4v.info/en/documents/download/75767

53 https://migrationnetwork.un.org/sites/default/les/network_statement_forced_returns_-_13_may_2020.pdf

54 https://www.ozy.com/around-the-world/the-coronavirus-is-driving-the-biggest-migration-in-the-americas-underground/291984/ and

https://lasillavacia.com/silla-llena/red-de-venezuela/los-migrantes-se-llevan-lo-peor-de-la-crisis-del-covid-19-76290;

55 UNODC (2020), Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tracking in Persons, available at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/Advocacy-

Section/HTMSS_Thematic_Brief_on_COVID-19.pdf

20 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

THE SPECTRE OF COVID-19

DRIVING FURTHER

DISPLACEMENT

There is the risk that the current pandemic will

cause further displacement in some places

where people do not feel protected. The

experience during the Zika and Ebola epidemics

suggest pandemics can cause displacement

as people look for protection elsewhere. Today,

some IDPs are already reported to be eeing

camps or informal settlements out of fear of

COVID-19, whereas internal migrant workers are

compelled to move back to rural communities

in large numbers due to the lockdown. And

diminished access by refugees and migrants

to local services and economic opportunities

in their host countries could trigger irregular

onward movements to other countries.

Moreover, in several countries, governmental

responses to the pandemic, with sometimes

heavy-handed or militarized approaches, have

led to social unrest and erosion of trust in

public authorities, especially in areas where the

social contract was already weak. Decisions to

postpone elections due to the pandemic or to

hold them despite the crisis might be exploited

for political gains and may increase political

tensions. The pandemic’s socio-economic

fall-out will also add stressors especially on

fragile countries. And while several conict

parties have committed to abide by the

Secretary-General’s call for a global ceasere,

in a number of conict settings, we have seen

armed groups stepping up attacks presumably

in efforts to take advantage of COVID-related

lockdowns. All these developments could,

in turn, lead to further displacement.

EPIDEMICS AS A DRIVER OF DISPLACEMENT

The Ebola epidemic, which spread through various

West African countries in 2014, provides some

insights into how epidemics can cause displace-

ment. An analysis by the Internal Displacement

Monitoring Centre (IDMC) from 2014 demonstrates

that the Ebola epidemic led to ve internal displace-

ment trends – these trends could, however, play

out both within a country’s border as well as across

international borders:

1. Fleeing the virus: Fear of being exposed to

the virus and falling ill due to lack of protective

measures has driven people to move as a pre-

ventive measure.

2. Fleeing quarantine: Displacement due to com-

munities eeing from quarantine, either before

or after quarantines were imposed.

3. Seeking health care: As rural areas tend to

be poorly served by health care facilities, this

forced many to ee to urban areas in need of

better health care.

4. Forced evictions and eeing stigma:

Patients who recovered could face stigma and

other challenges, including forced eviction,

forcing them to ee.

5. Fleeing violence and rights violations:

Violence and human rights violations as a

result of the epidemic could also force people

to ee.

56 https://www.internal-displacement.org/expert-opinion/displaced-by-disease-5-displacement-patterns-emerging-from-

the-ebola-epidemic

Source: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC)

56

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 21

EXAMPLES OF GOOD PRACTICES IN ADDRESSING THE PROTECTION

IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

• The Portuguese government announced that all migrants and asylum-seekers with pending residence

applications will be treated as permanent residents until 30 June 2020. This measure will grant migrants

full access to public social security systems, including health care.

• Ecuador has extended the deadline for Venezuelan migrants on its territory to apply for a humanitarian

visa until the end of the state of emergency.

• Immigration and international protection permissions issued by the government of Ireland due to expire

before 20 May are automatically renewed for a period of two months on the same conditions as the exist-

ing permission.

• Chile has set up an online system through which visas and stay permits are automatically extended for six

months, upon request.

• Uganda has waived the usual nes applied to visa overstayers for permits expiring during the lockdown

period.

• The European Commission adopted guidance on the implementation of relevant EU rules on asylum and

return procedures and on resettlement in the context of the coronavirus pandemic for its Member States,

underlying that any restrictions in the eld of asylum, return and resettlement must be proportional, imple-

mented in a non-discriminatory way and take into account the principle of non-refoulement and obliga-

tions under international law.

• According to UNHCR, several States have adapted their systems to carry out remote asylum processing

or have extended documentation and rights to remain pending capacities to carry out asylum procedures

safely. Some 82 States are adapting registration of new asylum applications by mail, phone, email or other

online mechanism, while some 86 States are adapting measures to issue new or extend the validity of

asylum documentation.

• New Zealand and Australia have extended the visas of the seasonal migrant workers to enable them to

remain in the countries, thus allowing them to continue working during the lockdown.

• Panama is offering shelter to stranded migrants while international travel restrictions are in place.

22 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

4. The future of human mobility

As mobility in many parts of the world has

ground to a halt, there are concerns that in

the mid- to long-term some of the current

movement restrictions could outlast the

immediate crisis. This could erode legal

obligations related to access to protection

under international human rights and

refugee law, as well as established practices

and norms around mobility. It also risks

reducing the benecial impact of migration

to countries of destination and origin.

Based on current developments, it is likely

that countries, as they gradually reopen

international borders, will impose additional

health requirements for travel, increasing the

need for health assessments, testing, screening,

immunization, treatment, and certication.

These requirments might disadvantage

vulnerable individuals, who may be stranded

or detained for indeterminate periods, have

to self-nance periods of quarantine or face

disproportionate health expenditures. Such

efforts could also drive more people into

irregular pathways. Furthermore, ad hoc

measures, put in place by governments

focused on containing the threat of the virus,

may engender an unworkable patchwork

of travel requirements, which would make

journeys more arduous and uncertain

than before and create new burdens on

private sector actors facilitating travel.

To prevent such requirements and ad hoc

measures from imposing overly burdensome

and prolonged constraints in international

travel and from running counter to their

commitments under International Health

Regulations (IHR, 2005),

58

it will be important to

ensure that such measures remain proportional

to public health risks and evidence-based.

It is equally important for countries to work

together to ensure common standards for

border management and travel which respect

human rights, privacy and data protection.

59

If some channels of migration are not reopened

once the crisis has subsided – whether due to

economic, political or public health risk concerns

– then the dynamics of migration are likely

to shift, with concomitant effects on people

and communities globally. Furthermore, the

recognition during this crisis of some migrant

workers as ‘essential’ should not serve as a

basis for a two-tier future migration system

purely based on essential and non-essential. Our

collective dependence on the vital contributions

of workers across sectors and industries with

a migrant or refugee background helps to

propel us to rethink human mobility, turn the

tide on anti-migrant discourses and make our

immigration systems pandemic-resilient.

58 WHO (2005), International Health Regulations, available at: https://www.who.int/ihr/publications/9789241580496/en/

59 IOM (2020), COVID-19 Emerging Immigration, Consular and Visa Needs and Recommendations, available at: https://www.iom.int/sites/

default/les/documents/issue_brief_2_-_ibm_052020r.pdf

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 23

Four basic tenets to advancing safe

and inclusive human mobility during

and in the aftermath of COVID-19

As this crisis unfolds, we are reminded again of

the importance of addressing human mobility

in a safe and inclusive way for the benet of

our own communities and economies, as well

as migrants, IDPs and refugees themselves.

This crisis is an opportunity to reimagine

human mobility for the benet of all while

advancing our central commitment of the

2030 Agenda to leave no one behind. It is

tting to build on the recognition of the vital

role played by people on the move to redouble

our efforts to combat discrimination against

them; to ensure that those in need of protection

are able to safely and promptly access it; to

health-proof human mobility systems; and to

strengthen global migration governance and

responsibility sharing for refugees, as already

envisaged by the Global Compacts on Refugees

and for Safe, Regular and Orderly Migration

and as spelled out in relevant international

human rights and refugee instruments.

To this end, the following four areas

are of particular relevance.

1. Exclusion is costly in the long-run whereas

inclusion pays off for everyone. As the

virus does not discriminate by nationality

or migration status, we cannot afford to

discriminate in our response. Exclusion

of people on the move is the very same

reason they are among the most vulnerable

to this pandemic today. Only an inclusive

public health response will enable us to

address the virus. This also requires ded-

icated efforts to ensure equitable access

to a COVID-19 vaccine for people on the

move, once such a vaccine becomes

available. Only inclusive socio-economic

recovery packages that include migrant

workers, refugees and IDPs will help our

economies restart and stay on track to

reach the Sustainable Development Goals.

2. Responding to the pandemic and protecting

human rights of people on the move are

not mutually exclusive. We should not let

our resolve to address this unprecedented

crisis undermine our collective responsibility

to respect the rights of people on the move

and protect them from further harm. As

many countries have demonstrated, travel

restrictions and border control measures

necessary to control the pandemic can

be safely implemented in full respect of

international human rights, international

humanitarian and international refugee

law, as well as labour standards.

3. No-one will be safe until everyone is safe.

The pandemic and its knock-on effects

will hit hardest those who were already

the most vulnerable before the crisis. This

includes people on the move in precarious

circumstances, as well as those in fragile

and conict-affected countries, in particular

women, children and older persons.

Lifesaving humanitarian assistance must

continue to reach persons in need even

during times of lockdown. Social services

24 POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

that prevent and respond to gender-based

violence, child abuse or exploitation must

continue to operate without disruptions.

All children on the move must continue

to have access to learning – whether by

extending access to no tech, low tech or

digital solutions while schools are closed or

safely reopening education services as soon

as possible. For all of us to be safe, access

to diagnostics, treatment and vaccines

must be universally accessible, without

discrimination based on migration status.

4. People on the move are part of the solution.

They are at the frontline providing health

care services and keeping our global

food production and supply chains going.

We need to value and recognize their

contributions to our societies. The best way

to do so is by facilitating the recognition

of their qualications; by ensuring that

human mobility remains safe, inclusive

and respectful of international human

rights and refugee law; and by exploring

various models of regularisation pathways

for migrants in irregular situations.

Furthermore, by keeping remittances

owing and bringing transaction costs as

close to zero as possible, we can help them

support their families and communities

in their home countries, contributing

to our collective efforts to achieve the

Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

No one country can ght the virus alone and no one

country can manage migration alone. But together,

we can do both: contain the spread of the virus,

buffer its impact on livelihoods and communities

and recover better, together.

POLICY BRIEF: COVID-19 AND PEOPLE ON THE MOVE 25